Text and performance: Pieter De Buysser

Music: Alain Franco

The question to what extent do people need history is a matter of public health. A shortage of history leads to ever-recurring stupidity. An excess of history, which is the danger of a commemorative festival, leads to history crumbling under its own weight, and so ends up killing the people’s vivid veins. Our era already has an inclination towards what has been. Nowadays, Europe is a museum; collecting, protecting, scraping off the cultural, moral and financial wealth of what was, cherishing and living off the wealth of the fathers. We live in antiquarian times, a non stop buffet of world expositions with wandering spectators having reached a mood in which revolutions or wars can not change anything anymore. In order to effectively resist this historical condition, we need history to be the power fuel, to be the plastic, the shaping power of the contemporary. WW1 can be considered as the turning point where Europe has lost it’s momentum, and started to traumatically turn into a moribund geriatric posterity preservation scheme.

The question to what extent do people need history is a matter of public health. A shortage of history leads to ever-recurring stupidity. An excess of history, which is the danger of a commemorative festival, leads to history crumbling under its own weight, and so ends up killing the people’s vivid veins. Our era already has an inclination towards what has been. Nowadays, Europe is a museum; collecting, protecting, scraping off the cultural, moral and financial wealth of what was, cherishing and living off the wealth of the fathers. We live in antiquarian times, a non stop buffet of world expositions with wandering spectators having reached a mood in which revolutions or wars can not change anything anymore. In order to effectively resist this historical condition, we need history to be the power fuel, to be the plastic, the shaping power of the contemporary. WW1 can be considered as the turning point where Europe has lost it’s momentum, and started to traumatically turn into a moribund geriatric posterity preservation scheme.

I will focus on one story that occured in WW1, a true story, and from which I will draw many different lines. Since it is a true story, I can fully use my imagination to pave future ways, to invent, to form, to knead, I just have to collect the facts and documents and present them in good order.

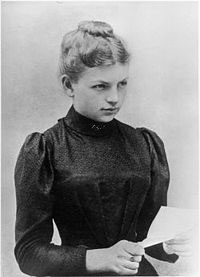

My guide and structure in this musical essay-story is miss Immerwahr. Clara Immerwahr (June 21, 1870 – May 2, 1915) was a German chemist, the first woman with a PHD magna cum laude in chemstry at a German university. A pacifist, she was the wife of Fritz Haber, fellow chemist. Fritz Haber was the scientist who developed the fertilizer that made Bayer the industrial giant it still is in the 21th century. This fertiliser still shapes our landscapes, agriculture and diet. The annual world production of his synthetic nitrogen fertilizer is currently more than 100 million tons. The food base of half of the current world population is based on his invention: the so called Haber-Bosch process. He won the Nobel prize for chemistry in 1919. Fritz Haber not only gave humanity the most powerful and widespread fertiliser, he is also the "father of chemical warfare" . He discovered, developed and deployed chlorine and other poisonous gases during World War I. They are also known under the name “Yperite”, or “mustard gas”. In early 1915, he suggested the simple idea: to release highly toxic chlorine gas so that it would drift across to the enemy trenches, where it would kill, maim and disable without an artillery bombardment. This strategy was so successful that up until today it has in every region and every period its followers. In a couple of days, they will probably start a another war over it.

Appalled, Clara Immerwahr came out in open opposition to her husbands work. She pleaded with him several times to cease working on chemical weapons.

Haber defended gas warfare against accusations that it was inhumane, saying “death is death, by whatever means it is inflicted.”

The first poison gas attack took place on April 22, 1915, on the Western front in Ypres, Belgium. Of the seven thousand casualties that day, more than five thousand died. Countless additional attacks resulted in the deaths of at least a hundred thousand soldiers on both sides. Haber was promoted to the rank of captain. He had personally overseen the first successful use of chlorine. He returned home from Ypres on the second of May 1915. There was a welcoming party in his honour in the garden of his house. When the party was over, Clara Immerwahr committed suicide in the garden, shooting herself in the heart with her husbands service revolver. She died in the arms of her 13 year old son. That same morning, Haber left for the Eastern Front to oversee gas release against the Russians. Haber left behind his grieving 13-year-old son Hermann, who had been the one to discover his dying mother. Later, Hermann left for the USA out of fear of the nazis. Soon after WW2, it became publicly known that Zyklon B, the gas the nazi’s used to exterminate the jews, was a derivate product, only made possible to be produced on an industrial scale thanks to research by his father in WW1. Clara’s son Hermann committed suicide in 1946.

99 years after Clara Immerwahrs death, the story of her life, epic and dramatic, will haunt the scene like a cloud.

I will also make a digression to the street I live in in Brussels: I live in the Boulevard d’Ypres in Brussels. A lot of asylum seekers hang out on the corner of my street, looking for illegal work or for 50 cents. Most of them are from Northern Africa, I’ve met several of them whose great-grandfathers were in Belgium during WW1, fighting in Ypres. Now they are coughing in the polluted air in the heavy traffic in Brussels. Breathable air is not a given thing anymore.

I will also draw a line towards Emmanuel Kant, the great philosopher of Enlightment who was so fond of mustard that every week he ordered his valet Lampe to prepare the strongest mustard for his master. And every week he wanted his mustard to be stronger. Mustard gas and Kants mustard have certain things in common. There is an indeniable relationship between an accelarating Kantian philosophy of modernity and progress and the genesis of a culture of efficiency, speed and massproduction. This relationship gave birth to the monstruous introduction of the first weapon of massdestruction: the use of mustardgas in Ypres, may 1915, in WW1.

The first use of gas in WW1 coincides with the advent of film, with the advent of the sound recording, with mass production and mass reproduction. In short: the use of gas in WW1 not only coincides but could be considered as a pars pro toto for a culture of the elimination of the unique bodily presence.

Craft has been chased down by massproduction, the movie, the sound recording, all that was singular and physical became abstract and uncountable. The uncountable is a universal mass, but untouchable and untangible like a gas. Alain Franco and I, on the contrary, will be physically present. (More and more I beleive performance to be the most urgent and subversiv artform of today: physical, vulnerable, naked, singular). Alain will play the piano and I will speak. Music is the art of making air into something material. There will be no amplification nor recordings. Alain will play music and probably introduce the pieces he plays. I will tell this essay-story. I will talk about gas, body to body fights, the origin of weapons of massdestruction and the elimination of the body as a unique singularity. I will tell the true story of Clara Immerwahr, her research, her breakfast habits, her husband and her son. I will tell about the emergence of the uncountable, of the simultaneous birth of massproduction and of mass extermination.

I will tell and by telling a new figure will arise, shaped by the sound and the body of Alain playing and me speaking.

The question in the title as to “Why miss Immerwahr didn’t wear a mask” will constantly fly through the performance space as if it was a tireless aircraft, until it will hit, and eventually, dissolve.